Introduction

We have known about workflows since the dawn of time. For decades, organizations have treated workflows as the central pillar of productivity. Managers were handed a set of resources—people, tools, budgets—and their job was to orchestrate those pieces into efficient, repeatable processes.

Traditional software reinforced this mindset: project management tools, ticketing systems, dashboards, and automation platforms were all built to help humans optimize how work gets done. The focus has always been on designing, refining, and enforcing workflows so the right steps happen in the right order.

In this model, success depends on a manager’s ability to anticipate needs, break tasks into parts, and manually coordinate the resources available. The software was tuned to make execution of those workflows easier for the people involved. We have all used and heard of JIRA, ServiceNow, Monday, Asana, and many, many others.

Evolution

As work grew more complex and interconnected, organizations began to realize the limits of rigid, top‑down workflows. A new model emerged: self‑organizing, self‑optimizing teams that form around outcomes rather than predefined processes.

It first started in the realm of project management. Agile and Scrum made this idea mainstream—empowering teams to decide how they work, adapt their process sprint by sprint, and continuously refine their collaboration without waiting for managerial directives. In project-based settings, these teams assemble with the right mix of subject‑matter experts to deliver a specific result and then disband once the goal is achieved.

In one of my previous lives, the company took that concept to an extreme. We completely re‑imagined the concept of the workplace, reporting lines, etc. Every SME (in the widest sense of the word) had a movable desk; the floor had power drops that allowed people to move around based on the need; and there were huddle spaces where people could get together. The team formed and organized itself for a particular delivery. Once completed, the team disbanded.

Those practices started making their way into continuous delivery or operations/maintenance environments as well. Even though the need to assemble and disassemble teams is not as frequent as with projects, higher autonomy allows for better operational agility. In fact, many militaries have discovered and encouraged that approach.

Instead of following rigid workflows, long‑lived teams take collective ownership of reliability, automation, incident management, and continuous delivery. They dynamically shift roles during incidents, iterate on processes as systems evolve, and make rapid local decisions using deep contextual knowledge. Software development practices like SRE, DevOps, and the Spotify squad model demonstrate how teams can continuously optimize themselves—evolving workflows organically based on real‑world signals rather than static managerial prescriptions. In these environments, self‑organization isn’t just a philosophy; it’s a practical necessity for scaling modern software operations.

What are the top prerequisites for self-organizing/optimizing team?

Successful self-organizing and self-optimizing teams don’t emerge by accident — they require a foundation of enabling conditions. Key prerequisites include:

- Clear Purpose: Teams need a well-defined outcome or goal, with measurable success criteria and constraints, so they can self-organize around meaningful results.

- Autonomy with Authority: Teams must have the power to make decisions about how they achieve goals, including control over workflows, tools, and internal roles.

- Cross-Functional Skills: Teams need the right mix of expertise to cover all aspects of their work, ideally with members who are T-shaped — deep in one area but broad enough to collaborate across boundaries.

- High Trust: Psychological safety and mutual trust, both within the team and from leadership, allow experimentation, rapid decisions, and open communication.

- Transparent Information: Access to metrics, historical data, system knowledge, and business context ensures that decisions are informed and effective.

- Continuous Learning Culture: Teams must regularly inspect and adapt their processes, learn from successes and failures, and continuously reduce toil and improve workflows.

- Supportive Leadership: Leaders define the what and constraints, remove obstacles, and guide rather than dictate, enabling teams to focus on the how.

When these conditions are in place, teams can self-organize around outcomes, continuously optimize their practices, and outperform traditional, rigidly managed workflows.

Using AI agents

If self-optimizing human teams outperform rigid workflows, the same principles can be applied — and amplified — in multi-agent AI platforms. In this setup, each AI agent functions as a specialized subject-matter expert (SME), optimized and contextualized for a specific domain. The agents are empowered to organize and optimize themselves, determining the most efficient sequence of actions, collaboration patterns, and resource usage to achieve a desired outcome. This allows the system to adapt workflows dynamically with unprecedented agility, far beyond what traditional human-managed processes can achieve.

The human role evolves accordingly. Rather than orchestrating step-by-step workflows, humans focus on:

- Goal Definition: Clearly specifying the intended outcome and success criteria, analogous to the “clear purpose” prerequisite for self-organizing teams.

- Agent Contextualization: Equipping AI agents with the right data, constraints, and domain knowledge — effectively ensuring cross-functional coverage and transparency.

- Guidance and Oversight: Setting boundaries and priorities while fostering a culture of safe experimentation, paralleling trust and supportive leadership in human teams.

- Monitoring & Feedback: Providing signals, metrics, and corrections that enable the agents to continuously learn and optimize their internal processes, similar to a continuous learning culture in human teams.

By shifting the human focus from micromanaging workflows to designing the environment, goals, and agent capabilities, organizations can leverage AI agents to form self-optimizing, high-performing “digital teams” that adapt in real time — essentially extending the principles of human self-organizing teams into the realm of intelligent automation.

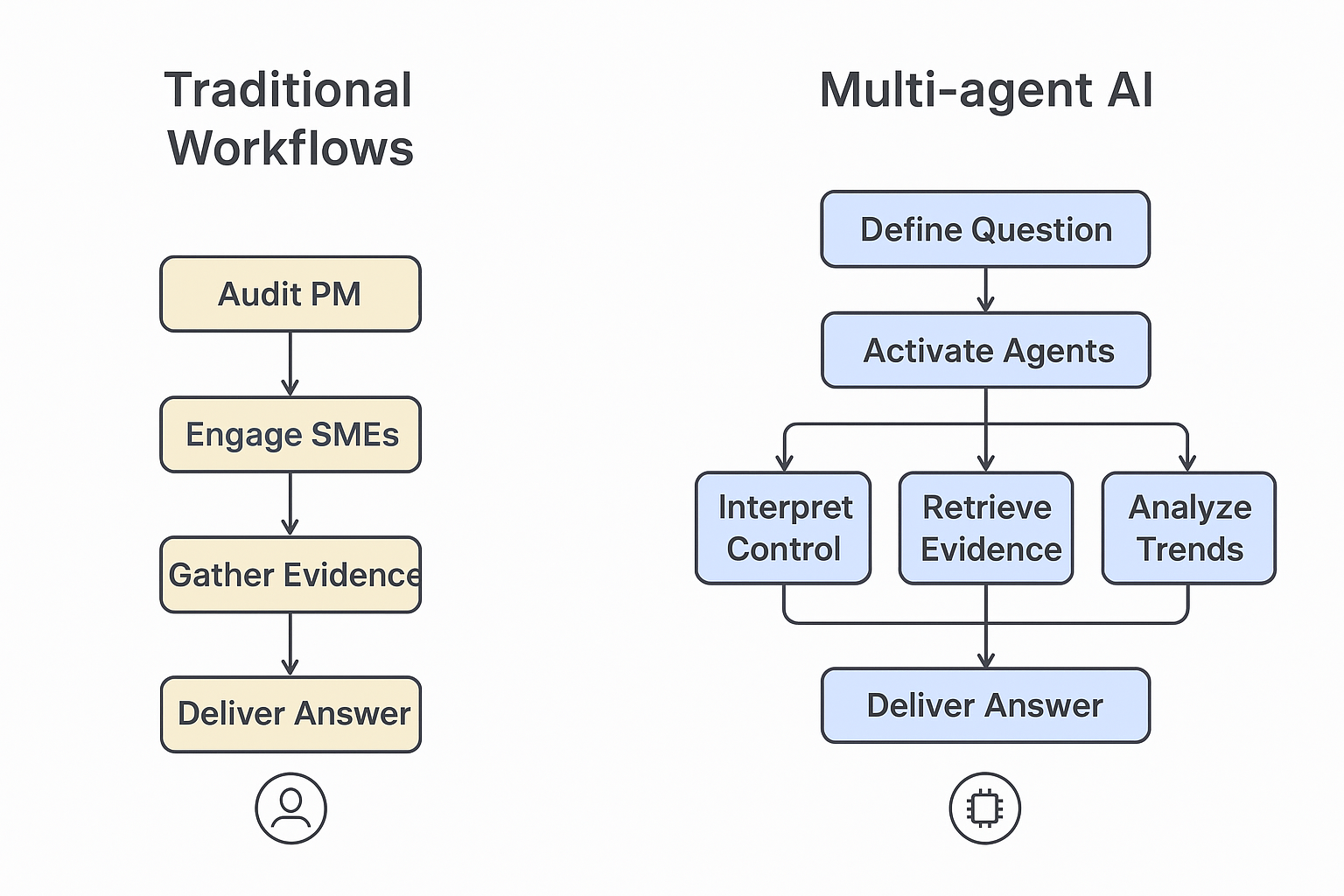

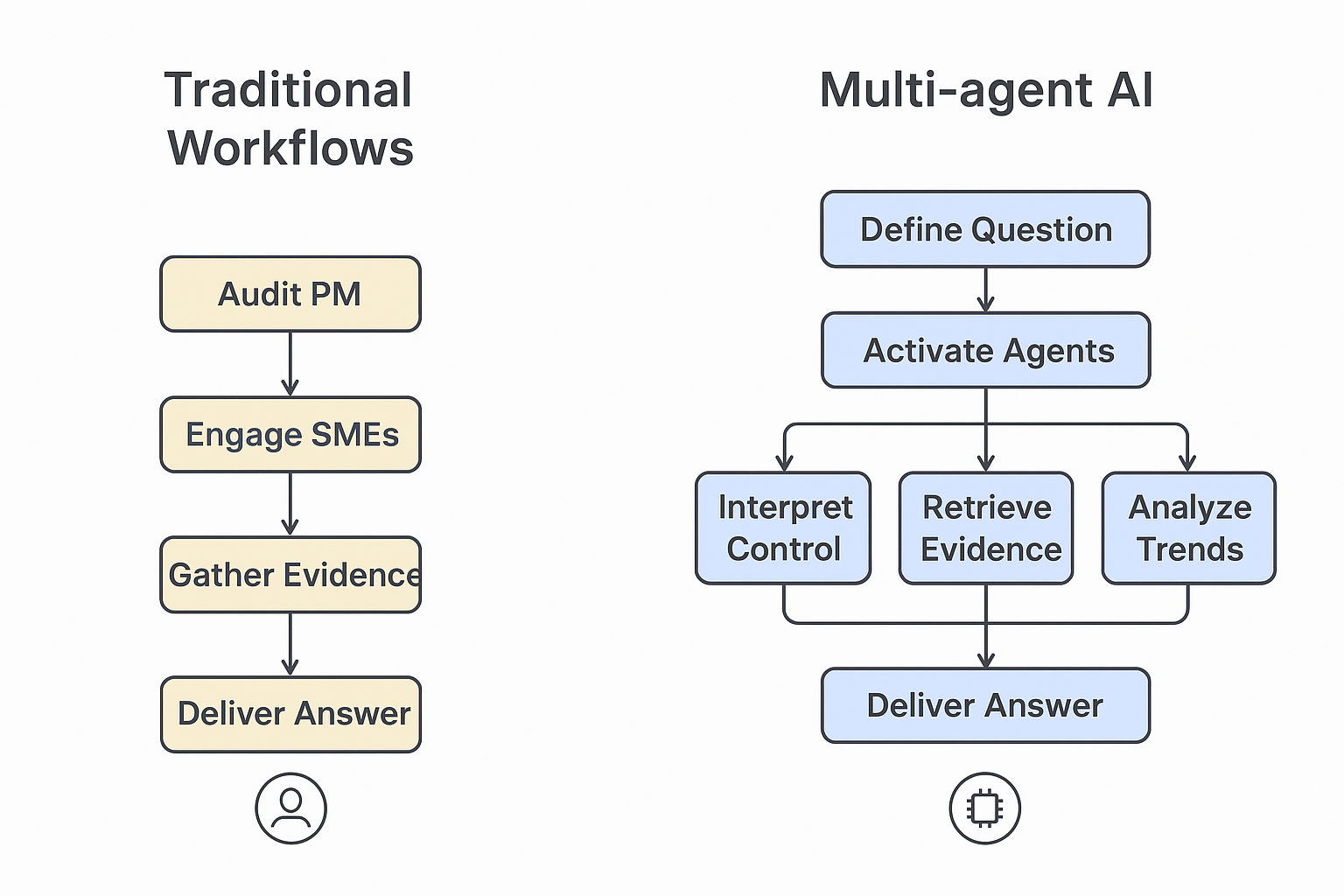

Consider the task of answering an audit question about a control’s performance.

In this scenario, the human’s role shifts from orchestrating the workflow to designing the problem space, contextualizing the agents, and defining clear success criteria. The system itself handles coordination, task sequencing, and evidence gathering — all in the background. The result is faster, more agile, and less error-prone delivery, demonstrating how multi-agent AI platforms extend the principles of self-optimizing teams to digital workflows.

Summary

In a world of multi‑agent AI platforms, the human role shifts from designing and supervising rigid workflows to defining outcomes, constraints, and context for self‑optimizing digital teams. Instead of breaking work into steps, assigning tasks, overseeing and enforcing processes through tools like ticketing systems and project boards, humans now act as outcome architects: they set clear goals, specify success criteria, encode guardrails, and provide the data and feedback AI agents need to collaborate autonomously. The real leverage no longer comes from micromanaging how work is done, but from shaping the problem space and environment in which specialized AI “SMEs” can organize themselves to deliver secure, reliable, high‑quality results. This extends to the GRC systems as well. We are starting to see more focus on “what?” rather than “how?”